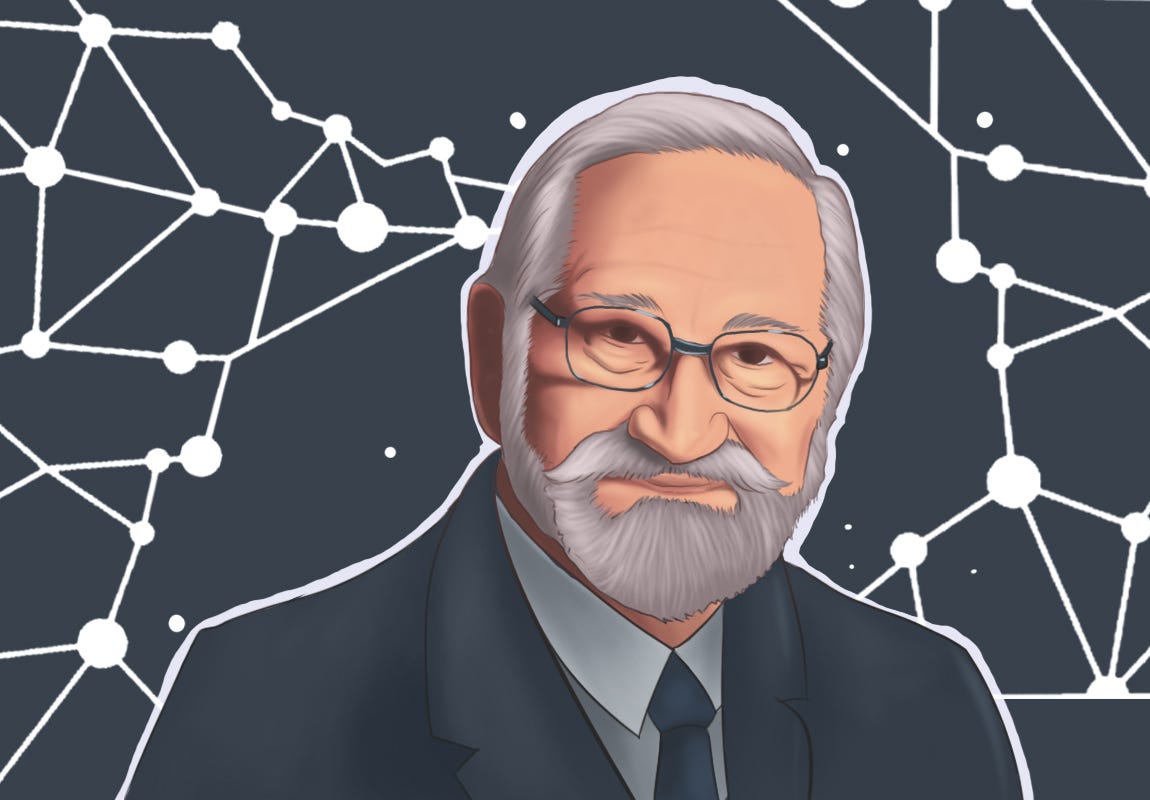

In one of our earlier articles, we discussed Jonas Salk and his polio vaccine. The vaccine developed by Jonas Salk contained a dead virus, which was injected into the human body using a needle. Albert Sabin, an American physician and microbiologist, came up with the second type of polio vaccine, known as the oral polio vaccine (OPV), or the Sabin vaccine, which is given orally. Like many scientists of that time, Sabin believed that only a live virus could guarantee immunity for a greater period.

Albert Bruce Sabin was born on August 26, 1906, in Bialystok, Russia, now a part of Poland. His parents were Jewish. During his childhood, Sabin received instruction in Hebrew and Yiddish. He also studied Russian with the help of a tutor. At the age of 15, Sabin's family migrated to the United States of America.

Sabin graduated from high school in Paterson, New Jersey. His uncle agreed to finance Sabin's education if he agreed to pursue a career in dentistry. Sabin spent two years preparing for dentistry at New York University. However, he switched to medicine after developing an interest in virology, thereby losing financial support. Scholarships and the income earned by doing odd jobs helped him to continue his education. Sabin received his Bachelor's degree in 1928 and then enrolled in the New York University College of Medicine. He received his MD in 1931, where he began his research on human poliomyelitis. It was Sabin's mentor, William Hallock Park, famous for his research into a diphtheria vaccine, who first urged Sabin to study poliomyelitis.

During the second world war, Sabin left his polio research to serve in the U.S. Army Medical Corps.

After his MD, Sabin served two years as a house physician at Bellevue Hospital in New York City. Then he travelled to the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine in London to conduct research. After a year, he returned to the United States and accepted a fellowship at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. He continued his research on poliovirus. Sabin and his colleague were able to grow poliovirus in brain tissue from a human embryo. He was the first researcher to demonstrate the growth of poliovirus in human nervous tissue outside the human body.

During the second world war, Sabin left his polio research to serve in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. While there, he investigated other diseases like insect-borne encephalitis and dengue, working on vaccines for both. After the war, Sabin accepted the position of research paediatrics professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and restarted his research on poliovirus.

To learn more about the virus, Sabin and his colleagues conducted autopsies on everyone who had died of polio within 400 miles of Cincinnati. The findings helped Sabin to prove that poliovirus first attacked the intestinal tract before moving on to the nervous tissues.

The Sabin oral polio vaccine was approved for use in the United States in 1960 and became the main defence against polio throughout the world.

While Jonas Salk started working on a killed-virus vaccine, Sabin began work on an attenuated live-virus vaccine. Sabin believed that a live, weakened virus administered orally would provide immunity over longer periods of time. By 1957, Sabin isolated the strains of each three types of polioviruses. These strains were not strong enough to produce disease but were effective in stimulating the production of antibodies. He then conducted preliminary experiments in the oral administration of these strains. The effectiveness of the new vaccine was conclusively demonstrated in extensive field trials. Sabin also cooperated with scientists from Mexico, the Netherlands and the Soviet Union.

The Sabin oral polio vaccine was approved for use in the United States in 1960 and became the main defence against polio throughout the world. Sabin also isolated the B virus and conducted research that led to the development of vaccines for sandfly fever and dengue. Sabin also held influential positions in organisations like the Weizmann Institute of Science, the U.S. National Cancer Institute, and the National Institutes of Health.

Albert Sabin died on March 3, 1993, in Washington, D.C.

Thank you for listening. Subscribe to The Scando Review on thescandoreview.com.

Happy Teaching!

Albert Sabin: The man who created the oral polio vaccine