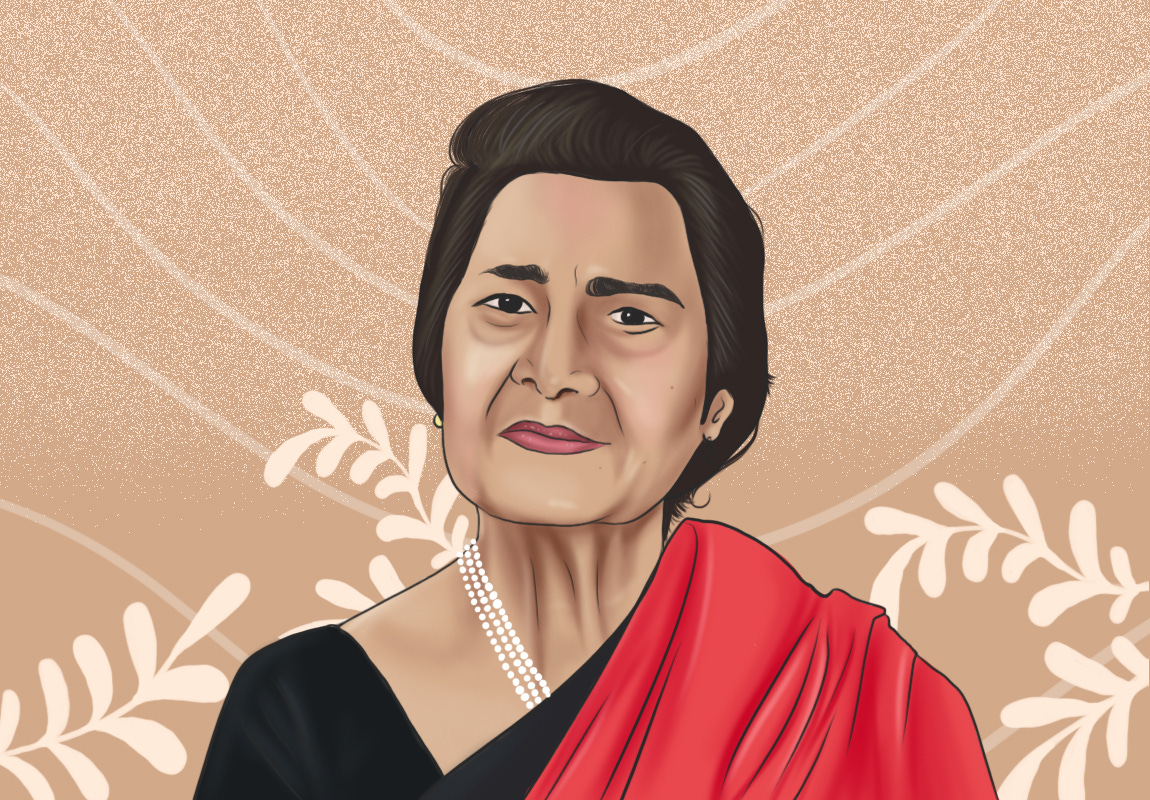

Amina Cachalia was a South African anti-apartheid activist, women’s rights activist and politician.

According to South African History Online, Amina was born on June 28, 1930, in a politically conscious family in Vereeniging, Transvaal. She was the youngest daughter of Ebrahim Ismail Asvat and Fatima Asvat. She was born as the ninth child in a family of eleven children. Her father, Ebrahim, was a companion of Mahatma Gandhi. Ebrahim was also the chairperson of the Transvaal British Indian Association, the forerunner of the Transvaal Indian Congress (TIC).

Amina’s family moved from Vereeniging to Newclare, Johannesburg, where her mother owned a property. She grew up without any consciousness about colour and race. She became aware of racial politics only when her family moved to Fordsburg, Johannesburg, where she was forced to attend an Indian school. There, she came under the influence of Mervy Thandray, according to South African History Online, a teacher who belonged to the Communist Party of South Africa. Mervy tried to make his students aware of the conditions in South Africa.

Amina’s father died when she was twelve, and Mervy became her mentor. When she was 15 years old, Amina was transferred to Durban Indian Girls High School. It was the time when the women’s passive resistance campaign was about to be launched from Durban. Amina was determined to take part in the campaign. However, the organising committee decided she was too young and frail to go to jail and prevented her from participating actively in the campaign. She remained in Durban until the end of the campaign in 1947 and returned to Fordsburg.

By that time, she decided not to continue with her formal education. Her family was struggling financially. According to Witz University’s official website, to improve their condition, she took up several jobs before finally settling into permanent employment as a secretary in a garment factory. She also became politically active. She joined the Transvaal Indian Youth Congress (TIYC) and participated in the classes conducted by members to learn about the political situation in South Africa. At that time, she had direct contact with the leaders of the African National Congress (ANC) who frequently visited TIC offices.

After joining the African National Congress, Amina actively participated in the Defiance Campaign by distributing leaflets, making home visits and recruiting volunteers.

When the TIC started offering South African students of Indian origin the chance to study in India, Amina became interested and applied. It was during the interview that she first met Yusuf Cachalia, secretary of the TIC, who later became her husband. When she applied for a passport, the government rejected her application, and she was unable to go to India. Instead, she worked for the Peace Council where she collected funds and organised meetings. She also became involved in Congress work and met people like Lillian Ngoyi and Helen Joseph who worked at the Industrial Council.

In 1948, Amina established the Women’s Progressive Union (WPU) which worked hand-in-hand with the Institute of Race Relations. She primarily focused on assisting women to become financially independent. This organisation, which was well supported by the Indian community, offered classes in literacy, shorthand and typing, baby care, dress-making, and music. It also offered training in nursing. With the help of the WPU, many women took up nursing as a profession. The Women’s Progressive Union worked for about six years.

After joining the African National Congress, Amina actively participated in the Defiance Campaign by distributing leaflets, making home visits and recruiting volunteers. On August 26, 1952, she marched in the Germiston batch led by Ida Mtwana. A total of 29 women participated in the march – eleven Indian, one coloured (Susan Naude), and seventeen African women. The group was arrested. Amina had a heart condition, so the rest of the women took special care of her.

According to South African History Online, during the early 1950s, Hilda Bernstein, a dynamic member of the South African Communist Party (SACP), and Ray Alexander Simons explored the idea of a women’s federation that would cut across colour and race. In 1954, they launched the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) with the help of Helen Joseph, Lillian Ngoyi, Josie Mpama, Ida Mtwana and Amina Cachalia. Lillian Ngoyi was elected the first president and Amina was the treasurer. The objective of the organisation was to oppose the proposed pass laws for women. (The Pass Laws Act required black South Africans over the age of 16 to carry a passbook, known as a dompas, everywhere and at all times).

FEDSAW held a protest march of women to the Union Buildings in 1955 with 2,000 women, mainly of African origin. After this march, FEDSAW decided to hold a national march with women of all races. On August 9, 1956, 20,000 women marched to the Union Buildings to present their petition against pass laws. According to South African History Online, these efforts by the FEDSAW succeeded in delaying passes for African women for a few years. Amina Cachalia also served as patron of the Federation of Transvaal Women (FEDTRAW) and was active in organising women in the liberation struggle.

Amina played a major role in the resuscitation of the TIC and the formation of the United Democratic Front (UDF) which protested against the South African Indian Council (SAIC).

At the end of 1956, police arrested 165 activists on the charges of treason. In March 1961, all charges were dropped. During the trials, Amina and her sister Zainab Asvat did support work for those on trial and for the families that had been left destitute by the removal of a breadwinner.

Organisations were banned after the treason trial. At that time, political activity went underground. According to South African History Online, activists were all regarded as threats to the state, and many were banned in 1963. In November 1963, Amina was banned for 5 years. She was recuperating from serious heart surgery at that time. Her husband, Yusuf, was also placed under house arrest at that time.

During the ban, Amina was restricted from social and political gatherings. She was not allowed to leave the magisterial district of Johannesburg and could not enter any publishing house or educational premises. When the banning order was about to expire, she was served with one after another.

Amina remained under the ban for over 15 years. These bans that restrained her from associating freely with other people put an end to her political work. According to South African History Online, she played a key role in planning and executing the escape of Arthur Goldreich, Harold Wolpe, Mosie Moolla and Abdulhay Jassat from Marshall Square prison in 1963.

Amina’s ban ended in 1978. She played a major role in the resuscitation of the TIC and the formation of the United Democratic Front (UDF) which protested against the South African Indian Council (SAIC). When the African National Congress Women’s League (ANCWL) was revived in the 1990s, she served on the committee of the PWV [(union of Pretoria, Greater Johannesburg (Witwatersrand) and Vaal Triangle (Vereeniging)] region. She was also elected a Member of Parliament for the National Assembly in the first democratic elections in 1994. She was offered an ambassadorial posting, which she rejected.

In 2004, according to South African History Online, the South African government conferred The Order of Luthuli in Bronze to Amina Cachalia for her lifetime contribution to the struggle for gender equality, non-racialism and a free and democratic South Africa.

Amina Cachalia passed away on January 31, 2013, in Johannesburg, Gauteng Province.

Now put on your thinking hats and think about the following questions for a couple of minutes.

Can you think of how the Women’s Progressive Union helped women to become self-sufficient?

How would you describe the contributions of Amina Cachalia to the women’s rights movements in South Africa?

Write down your thoughts and discuss them with your students, children, and your colleagues. Listen to their views and compare them with your own. As you listen to others, note how similar or different your views are to others’.

Thank you for listening. Subscribe to The Scando Review on thescandoreview.com.

Happy Teaching!

Amina Cachalia: South Africa’s anti-apartheid stalwart